The U.S.-China Trade War: A Derisking, Not Decoupling

Decoupling from China is too hard. Here’s why.

In my last post, I discussed the U.S.-China investment war. In this piece, through the lens of a venture investor, I will address the history and current state of the trade war and highlight new opportunities for entrepreneurs and venture investors.

How we got here

China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, committing to a comprehensive set of economic reforms that included tariff cuts for imported goods and intellectual property (IP) protections. Since then, China's economy has grown fivefold and is now the world's second largest by GDP. The annual trade volume between the U.S. and China has grown from a few billion dollars to hundreds of billions of dollars.

However, things took a turn in 2018. The Trump administration imposed tariffs ranging from single digit percentages to 25% on $360 billion worth of Chinese imported goods (about 67% of total U.S. imports from China) between 2018 and 2020. China responded by imposing tariffs on about $60 billion of U.S. imports. The Biden administration continued the tit for tat by implementing several new industrial policies, including the CHIPS and Science Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act,

As we approach the fifth year of the trade war, where do we stand? Surprisingly, trade in goods between the U.S. and China climbed to a record in 2022, exceeding the record set before the trade war started.

Where this is going

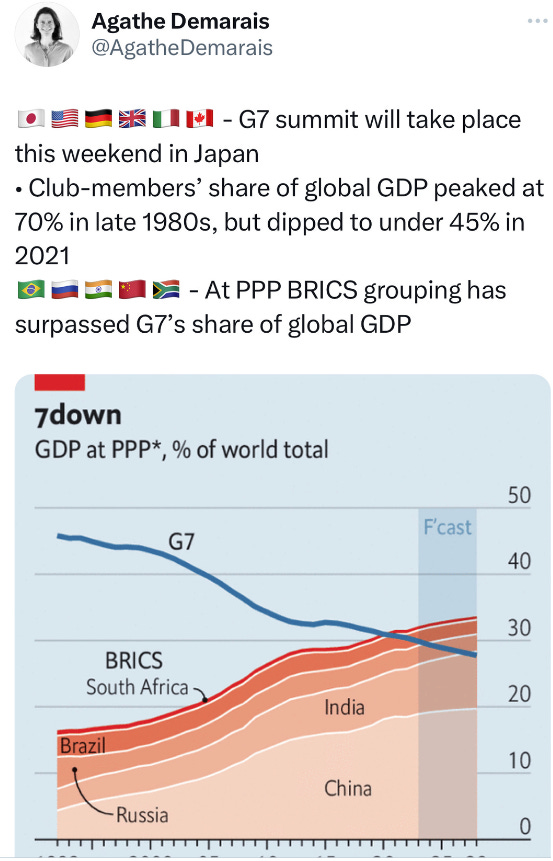

The past five years of the trade war suggest that attempts to separate the U.S. and China in global trade have overall been less effective than anticipated. The media headlines have also recently switched from calling it a “decoupling” to a “derisking” when describing the U.S.’s approach to China. Some think “derisking” is just “decoupling in disguise” while others see it as a more practical approach for what U.S. and China hope to achieve. I fall into the latter category. I see three key challenges that will make it extremely difficult for the U.S. and many other regions to decouple from China fully in global trade. Ultimately, the U.S. and China will need to find a way to balance their focus on preserving national security and maintaining a healthy economic relationship, and derisking can accomplish that.

It will take decades for new regions to build highly efficient manufacturing clusters, enabled by self-sufficient supplier ecosystems like those in China

Recently, there has been a surge in the media introducing terms such as re-shoring, friend-shoring, and multi-shoring, all with the common goal of reducing reliance on China's supply chain. While it is valuable to invest in a more diversified and thus more resilient supply chain strategy, I think it is equally important to acknowledge the strength of China’s supply chain when companies assess the likelihood of achieving their supply chain goals. It may take decades for them to fully transition away from China's supply chain.

One case in point is electronics. 90% of the world’s electronics are produced by Shenzhen, where almost any electronic component supplier and manufacturing equipment can be found. Apple has been leading the effort to move its supply chain away from China, but with very limited success. Bloomberg estimated that by 2030, Apple would shift just 10% of iPhone production outside of the country.

Apple established factories in countries such as India and Vietnam, but most operations in these regions today are classified as FATP (Final Assembly, Test, and Pack), which requires Apple to produce components in China and then send them to these regions to assemble the product. And still the assembly process is often supervised by experts from China with deep manufacturing know-how anyway. Therefore, it’s not much of a decoupling when the parts needed for assembly are made in China and the expertise needed to assemble them is imported, so to speak, from China, as well. That said, companies can avoid U.S. tariffs on China-imported products when FATP is handled in another country, to say nothing of taking advantage of local tax breaks and cheap labor in places such as India and Vietnam.

Apparel is another example. In a prior post, I wrote about Shein's ultra-fast fashion model. Shein concentrates its supply chain mainly in Guangzhou, which contains the most comprehensive apparel suppliers and manufacturers ecosystem in the world, from fiber production, yarn spinning, fabric manufacturing, textile wet processing, to embroidery. Most suppliers are within a five-hour drive of each other. Similar to Shenzhen's role in electronics, Guangzhou's self-sufficient supplier ecosystem enables Shein to have a shorter time to get its products to market, a higher capacity utilization that reduces unit costs, and better economies of scale, which leads to adding on average about 6,000 new items every day.

Competing with Guangzhou or Shenzhen is not just about having cheap labor but more about rebuilding an entirely vertically integrated supply chain from raw materials to manufacturing equipment and having the manufacturing know-how to turn it into a highly efficient manufacturing cluster. TSMC is a recent example that shows how challenging it is to relocate supply chains.

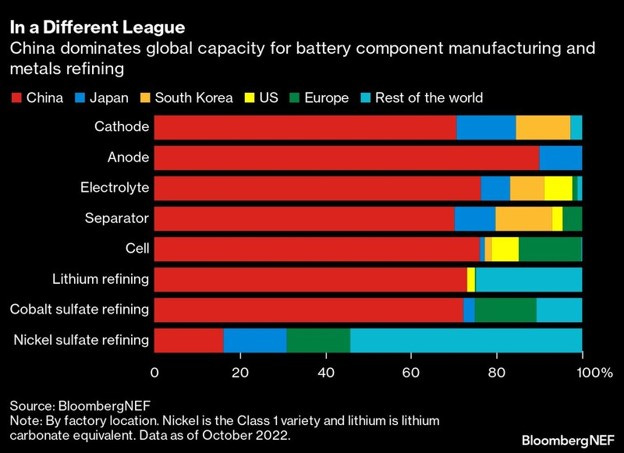

The central role that the Chinese government plays in coordinating nationwide resources reinforces China's status as a manufacturing superpower

A combination of in-state planning at the macro level (socialism) and market mechanism at the micro level (capitalism) makes China very effective at coordinating national resources in the industries it wants to grow. The electric vehicle (EV) industry is a prime example. The Chinese government acknowledged the importance of electrifying mobility over a decade ago and has been consistently prioritizing EV development over the past decade. From 2009 to 2022, the government provided over $29 billion in subsidies and tax breaks. Last year, it spent $546 billion investing in clean energy, which accounted for nearly half of the world's low-carbon spending. Before any consumer adoption back in the 2010s, to help domestic EV companies stay in business, China handed out procurement contracts with its public transportation systems, from buses to taxis. Today, state-owned installers have built more than 1.8 million public chargers to accelerate domestic adoption, compared to 1 million by the rest of the world. Government support has given not only domestic EV companies but also battery makers a head start. China has achieved many technical breakthroughs in battery manufacturing, with leading the way in both lithium-ion and sodium-ion batteries and controlling the majority of the refinery capacity.

Solar photovoltaic panels (PV) are another example where government influence has accelerated both the development and the adoption of solar PV in China and globally. The country today controls over 75% of every key stage of solar PV manufacturing and processing, from polysilicon production to soldering finished solar cells and modules onto panels, globally.

I assume that the same pattern will recur in other strategically critical sectors in China. The Chinese government's power to plan and allocate national resources reinforces the country as a manufacturing superpower, making it even harder for other regions to catch up and for the rest of the world to abandon China in global trade completely.

China is a major consumer for many Western companies, so economic decoupling isn’t exactly in their interest

China is one of the largest markets for many U.S. corporations, if not the largest. Starbucks founder Howard Schultz visited his Chinese employees and stores in April in Beijing as Starbucks plans to open one store nearly every nine hours in China for the next three years which will push China past the U.S. to become Starbucks' biggest market by 2025. And over the past few months, despite the geopolitical tensions, top U.S. corporate CEOs, including Tim Cook, Elon Musk, and Jamie Dimon, all rushed to visit China and show their eagerness to stay in the China market. For Musk’s Tesla alone, the high stakes are obvious, with China accounting for 60% of global EV sales last year. China represents close to 20% of Apple’s net sales in 2022 and also generates over 60% and 20% revenues for chipmakers Qualcomm and Nvidia, respectively. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang has warned that export controls imposed by the U.S. could cause “enormous damage” to American companies and is also planning to visit China very soon.

It is hard to isolate China as a way to keep its potential economic dominance in check. But for those who want that, there may be no reason to, not when domestic consumption in China is weak right now, and the government is eager to keep cross-border trade flows open. In the long term, participating in global trade is the most effective ways for China to circulate more RMB into the world currency system, thus improving RMB stature as a premier currency.

Suggestions for entrepreneurs and investors

Despite trade hiccups and restrictions along the way, I’m optimistic that trade between the U.S., China, and the rest of the world will continue to expand and new trade sectors will emerge given the complex interconnectedness I’ve described above. For entrepreneurs and investors seeking to capitalize on global trade during turbulent times like the present, below are three areas that I think could be interesting for startup founders and investors to consider.

In cross-border, B2B will take share from B2C

In a prior post, I wrote about China cross-border 3.0, in which conglomerates such as Shein, Alibaba, and Pinduoduo (Temu) are using the online shopping models they created in China to shape consumer purchasing behavior overseas. I think geopolitical tensions, and their focus on data privacy issues and other sensitive information, will keep the B2C sector in the hands of conglomerates. After all, it’s a big-money, big-legal-department game. For founders, the play may be in the next generation of B2B platforms instead. In a cross-border context, B2B refers to merchants —in this case, merchants in the West —sourcing from overseas suppliers in the East or the regions with supply chain advantages and then reselling to distributors in the West or direct to consumers. Though still at the risk of trade tariffs, the fact that overseas suppliers do not have a direct relationship with local consumers protects them from the aforementioned data privacy and ownership regulations. At the same time, local wholesalers and merchants can still benefit from buying bulk at factory prices and generating high margin in resale.

Diversification and flexibility will take priority in constructing a supply chain strategy

Over 40% of global trade today is concentrated into small circles of relationships among countries, meaning that importing economies rely on three or fewer nations for their share of global trade. While I don’t think moving the supply chain away from China is easy, I do believe in lowering exposure risk by exploring a “China plus others” supply chain strategy to avoid sudden disruptions. Services that can help businesses source more cost effectively from different regions while assembling a resilient and diversified supplier pool will be in high demand.

New alliances will emerge, which will create new playgrounds for global economic growth

The changing world order is reforming new alliances. For example, China’s growing role in the Middle East can hardly be ignored. I anticipate this will give rise to new economic blocs. There may be fewer trades among the blocs, especially in politically sensitive sectors. However, there is likely to be a deepening of trade within each bloc, supported by trusting relationships. Companies that either support this new alliance formation or ride the growth of trade volume within new economic blocs will enjoy tailwinds.

If you are interested in discussing startup opportunities in the three areas outlined above or having other ideas to facilitate global trade, let’s definitely get in touch and chat!

You are right. 您说的对。

Basically the USA and China should focus on cross border trade and not cross border investment. China will never allow expatriation of capital investments or profits. It's a mercantilist state capitalist dictatorship, but as a mercantilist IS a trading state. USA is the world's fourth largest Chinese country. Both the USA and China LOVE money, wealth. They simply have too much in common culturally to wage a true cold war. 改革开放加油!